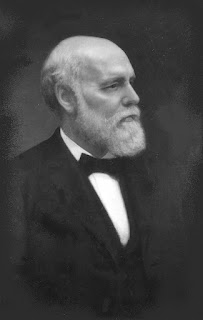

During the years just before Meta Chestnutt arrived in Nashville, the State Normal College went through two moments of crisis. Both episodes, as they turned out, effectively strengthened the school. The first related to the near-constant concern of many institutions of higher learning: money. Since the founding of the college in 1875, the State of Tennessee, impoverished as a result of the Civil War, contributed nothing to it. The college was able to survive only because the University of Nashville, its parent institution, provided the facilities and the Peabody Education Fund covered virtually all of the operating costs. Under those conditions, the school could subsist, but it could not thrive and grow. In 1880, President Eben Stearns (pictured here) and Barnas Sears, the general agent for the Peabody Education Fund, visited Georgia and considered an offer from state leaders to bring the school to either Athens or Atlanta. They promised that, unlike Tennessee, Georgia was willing and able to provide funding. Naturally, the prospect of moving the school to another state presented its own set of problems. But before any more plans could be made, wealthy residents of Nashville, alarmed by the news about a possible move, immediately contributed $4,000 and promised there would be more. Soon afterwards, in 1881, the Tennessee legislature appropriated $6,000 for the college with a pledge to support it in the future. The state kept its promise. In fact, from 1881 until 1905, the General Assembly appropriated $429,000 for the college. During the same time period, the Peabody Education Fund contributed something close to the same amount. As a result, the school was able to develop as never before.[1]

In 1883, several new graduates of the college appeared before the Tennessee State Board of Education. In a petition with seventeen separate complaints they criticized their alma mater, especially the leadership of Stearns. Many of the items on the petition echoed the grumblings of some of the school's professors: some of the faculty were insufficiently-trained; alumni and faculty were denied power to influence the direction of the school; and textbooks were too few and of poor quality. For his part, President Stearns refused to respond. He was able to remain quiet mainly because he had the confidence of the state board as well as the trustees of the Peabody Fund. And, many of the current students expressed their support for the administration. The crisis came and went. But this was partly because, until his presidency ended with his death in 1887, Stearns effectively addressed almost every point in the petition and increased the pace of needed change.[2] Consequently, when Chestnutt began her studies in Nashville, the State Normal College was better than it had ever been before.

Notes

[1] Paul K. Conkin, Peabody College: From a Frontier Academy to the Frontiers of Teaching and Learning (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2002), 122-25; Franklin Parker and Betty J. Parker, "Peabody Education Fund in Tennessee," in Tennessee Encyclopedia of History & Culture, ed. Carroll Van West (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 1998), 725-26.

[2] Conkin, Peabody College, 125-128.

No comments:

Post a Comment