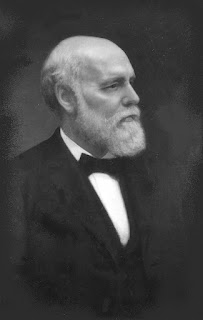

The most likely answer has everything to do with her time in Nashville, from 1886 until 1888. During her student days at the State Normal College, Chestnutt found herself in a thriving church environment. For example, she would have heard the the preaching and teaching of David Lipscomb (pictured here) and E. G. Sewell, co-editors of the anti-instrument and anti-society Gospel Advocate magazine, published from Nashville.

In 1870, Lipscomb realized he needed help in producing the Advocate. He asked Sewell to edit the magazine with him, and from that time until Lipscomb's death forty-seven years later, the two men worked together. Each was a powerful voice for the distinctive viewpoint of the emerging Churches of Christ. In addition to their teaching through the Advocate, the two leaders preached to thousands of people in Middle Tennessee and beyond. During those years, Sewell help to establish the Woodland Street Christian Church in East Nashville. He preached for the congregation for twelve years and for a time served as one of the church's elders. Lipscomb was also an active as a leader among Restoration Movement churches in and around Nashville. In 1891, he and James A. Harding would establish the Nashville Bible School, known today as Lipscomb University.[1]

By the end of 1889, Lipscomb looked back over the past twenty years with pride: "In 1869 we had one church in Nashville with a membership of about 500. Now we have five churches and three promising missions with a membership of over 2,500 in the city."[2] The five congregations Lipscomb mentioned were the old first church, established in the mid-1820s, with its brand new building on Vine Street; North Nashville Christian Church (organized in 1882); Woodland Street in East Nashville (1883); and the Foster Street and South Nashville congregations, both established in 1887.[3]

Notes

[1] On David Lipscomb, see H. Leo Boles, Biographical Sketches of Gospel Preachers (Nashville: Gospel Advocate Company, 1932), 243-47; and Robert E. Hooper, "Lipscomb, David (1831-1917)," in Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement, 480-82. On E. G. Sewell, see Boles, 238-42; and David H. Warren, "Sewell, Elisha Granville (1830-1924)," in ESCM, 680-681. See also David L. Little, "Gospel Advocate," in ESCM, 361-63.

[2] "From the Papers," Gospel Advocate 31 no. 47 (November 20, 1889), 737.

[3] "History of the Christian Church in Nashville," Daily American (Nashville), (January 26, 1890), 10.