Once there was "Old Blogger." It was frustrating at times. But you came to expect certain problems, and when they cropped up, you weren't surprised and you coped.

Today, I was forced into joining up with "New Blogger." In this case, "New" refers to previously-unknown and more-frustrating problems. Specifically, I have a not-great, but not-that-bad something that I cannot post straight from a Word document. Also, I noticed that some previous personal comments have been downgraded to "anonymous."

Like most lifers in the Church of Christ, I can handle just about any imperfect system, provided it will hold still. Now, like a winter-weary southerner making ready to move away from New England (so he can endure tough winters in Texas?) I'm planning to move "Frankly Speaking" elsewhere.

Suggestions? Advice? Experiences?

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

Monday, January 29, 2007

Joe Lemmons

Yesterday my mother emailed me: “Joe Lemmons died today . . . He was 85. We will pray for them.”

Every person has an unwritten list of names, each entry filled with significance. The name Joe Lemmons is on my list.

When I was born in 1963, my parents were relatively-new Christians. They had come to New Jersey in 1961 when the U. S. Air Force transferred my father there from Alaska.

Soon after they moved to the Garden State, my parents became members of the Church of Christ at New Egypt, New Jersey. I made it to my first Lord’s Day service all of five days old. Joe Lemmons was my first preacher.

Joe and his wife, Lois, were about ten years older than my parents. My father had one older sister, but never any brothers. My mother had no sisters or brothers. So in certain ways, I think, Joe and Lois became some of those older siblings my folks never had before.

Joe was a southerner and a graduate of Harding College. He had come to New Jersey back in the day when places like the Northeast were still seen by a lot of people in the Churches of Christ as a domestic mission field. He prayed to God and nurtured others. He preached sermons, taught classes, conducted personal studies and, of course, an annual Vacation Bible School. (My older sister always thought it was cool that, whenever we sang “Booster, Booster” at VBS, her otherwise-dignified preacher would be transformed into a grouchy rooster). In the field behind our new church house, he played softball with the rest of the congregation.

I was in the second grade when my father was transferred to Altus Air Force Base in Oklahoma. When we moved, we said our good-byes to the Lemmons Family and to the church that my family had been a part of for ten years. Joe and Lois stayed in that part of the country for many more years, praying to God, strengthening others, telling the story.

Today I’m praying for Lois Lemmons, for the couple's children, and for all of their extended family. I pray that all of them will be given comfort and peace. I’m also thanking the Lord today; thanking Him for the life of Joe Lemmons.

“Then I heard a voice from heaven saying to me, ‘Write: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.’ ‘Yes’ says the Spirit, ‘that they may rest from their labors, and their works do follow them.’” Revelation 14:13

Every person has an unwritten list of names, each entry filled with significance. The name Joe Lemmons is on my list.

When I was born in 1963, my parents were relatively-new Christians. They had come to New Jersey in 1961 when the U. S. Air Force transferred my father there from Alaska.

Soon after they moved to the Garden State, my parents became members of the Church of Christ at New Egypt, New Jersey. I made it to my first Lord’s Day service all of five days old. Joe Lemmons was my first preacher.

Joe and his wife, Lois, were about ten years older than my parents. My father had one older sister, but never any brothers. My mother had no sisters or brothers. So in certain ways, I think, Joe and Lois became some of those older siblings my folks never had before.

Joe was a southerner and a graduate of Harding College. He had come to New Jersey back in the day when places like the Northeast were still seen by a lot of people in the Churches of Christ as a domestic mission field. He prayed to God and nurtured others. He preached sermons, taught classes, conducted personal studies and, of course, an annual Vacation Bible School. (My older sister always thought it was cool that, whenever we sang “Booster, Booster” at VBS, her otherwise-dignified preacher would be transformed into a grouchy rooster). In the field behind our new church house, he played softball with the rest of the congregation.

I was in the second grade when my father was transferred to Altus Air Force Base in Oklahoma. When we moved, we said our good-byes to the Lemmons Family and to the church that my family had been a part of for ten years. Joe and Lois stayed in that part of the country for many more years, praying to God, strengthening others, telling the story.

Today I’m praying for Lois Lemmons, for the couple's children, and for all of their extended family. I pray that all of them will be given comfort and peace. I’m also thanking the Lord today; thanking Him for the life of Joe Lemmons.

“Then I heard a voice from heaven saying to me, ‘Write: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.’ ‘Yes’ says the Spirit, ‘that they may rest from their labors, and their works do follow them.’” Revelation 14:13

Saturday, January 27, 2007

N.T. Wright on Just War and the U.N.

I was mildly complaining at another blog that in his new book on Evil and the Justice of God, N. T. Wright never mentions if he thinks there is anything like just war. If he does, I haven’t found the passage. Wright does criticize the actions of the U.S. and Britain following the attacks of 9/11 as wrong-headed reactions to what certainly was evil.

Because that’s where Wright begins his book, and because he pushes the point that evil cannot be destroyed by bombs and military prowess, I waited for him to throw in a caveat that mentioned something like World War II or someone like, say, Hitler. He doesn’t. And so I wondered.

Anyway, more recently, I did come across a short article where Wright explains his conviction that even violence can be morally justified. He also mentions his belief that what is really needed is a “strong United Nations” that can either be or can sanction “a credible international police force.”

It’s an understatement to say that for most people in the United States, that last part sounds impossible and ludicrous. On the other hand, I certainly agree with his point that the U.S. and Britain simply cannot act as a “credible police force in the world, especially in the Middle East.”

It only takes a couple of minutes to read the article. So take a look and tell me what you think.

Because that’s where Wright begins his book, and because he pushes the point that evil cannot be destroyed by bombs and military prowess, I waited for him to throw in a caveat that mentioned something like World War II or someone like, say, Hitler. He doesn’t. And so I wondered.

Anyway, more recently, I did come across a short article where Wright explains his conviction that even violence can be morally justified. He also mentions his belief that what is really needed is a “strong United Nations” that can either be or can sanction “a credible international police force.”

It’s an understatement to say that for most people in the United States, that last part sounds impossible and ludicrous. On the other hand, I certainly agree with his point that the U.S. and Britain simply cannot act as a “credible police force in the world, especially in the Middle East.”

It only takes a couple of minutes to read the article. So take a look and tell me what you think.

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

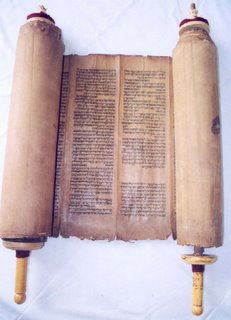

Teaching about the Documentary Hypothesis

The Old Testament class I teach is billed as a first-year college course. As such, it should overview the content of the Old Testament, plenty of material for a semester’s worth of study. And that’s why I thought long and hard before doing what I did last night.

The Old Testament class I teach is billed as a first-year college course. As such, it should overview the content of the Old Testament, plenty of material for a semester’s worth of study. And that’s why I thought long and hard before doing what I did last night.A little background. Because the class meets at night, it’s an older group than I usually have. Many of the students are workaday professionals. Night time is their time to take a college course. The class includes a veteran preacher, a real estate agent, a physician, and a high school science teacher.

Because it’s made up of a lot of eager and accomplished people, I made the decision to introduce the class to the old “Documentary Hypothesis of the Pentateuch.” If that’s an expression you haven’t seen before, you can read about it here.

There's much about the theory to criticize. But I do think it’s significant because it has been significant in modern study of the Old Testament, not to mention the entire field of biblical research. So last night I walked the class through the rise and development of the hypothesis, some of the basis for its appeal, and some of the problems it has.

Before getting into that, though, I told them about my apprehension and about my confidence in their ability and maturity. I also told them that this was the most significant topic in the field of Old Testament higher criticism, the only one we would really get into all semester. If they didn’t like this section or started to feel lost, they could be confident that we wouldn’t be doing anything like this again.

I was fairly well-prepared to teach the material. I used visuals on the screen as well as handouts. From what I could tell, it wasn’t too much.

I closed by saying that there are problems with the goals, origins, development and conclusions of the hypothesis (deep breath) and that a good case can be made for the tradition that Moses is author of the “Books of Moses.” At the same time, it’s fair to acknowledge that Moses may have used oral and/or written sources (especially in writing Genesis), and that the received Pentateuch seems to include some editorial comments that come from a much later time. A good example is found in Genesis 36:31, where, in a list of ancient Edomite kings, the text explains that this was “before any kings reigned in Israel.”

Now, I have a lot of questions.

One is, In Christian universities, Bible colleges, and seminaries, what are the professors saying these days about the Documentary Hypothesis? I’m curious about the state of its influence and any discussion of it. My suspicion is that, in the O.T. classes in more conservative schools, there’s still a unit on what the hypothesis is and why it’s wrong. The better-read teachers in such schools probably (and should) bring in the newer voice of narrative-critical study which demonstrates literary artistry across huge sections of the Torah.

Clearly, though, the hypothesis is still the working assumption of many Old Testament specialists today. Even the decidedly-evangelical Word Biblical Commentary series includes volumes that proceed on its premise! All that to say, it doesn’t seem quite dead.

I have to confess that although the history of how it developed intrigues me, the hypothesis itself seems like a literary version of Darwinism, hopeless and unconvincing. (Yes, I understand about the philosophical connections one can draw between Darwin and Wellhausen).

Anyway, what are your thoughts? Responses? Criticisms? I’m curious about what other students and teachers and searchers think.

Monday, January 22, 2007

Tagged, Tellin', Taggin'

I got “tagged” by Wade Tannehill. Now I’m supposed to tell about five odd or interesting things about me that people would not ordinarily know. Here goes:

1. For starters: Some of the more interesting-or-odd things about me I just won’t tell here because they involve me breaking the law, acting immorally, being idiotic, or some combination thereof.

I sometimes think that God sends out Jack Bauer-type angels to protect young men during those high-testosterone years. (Their show would be called “At Least 24 Months”). Suffice it to say that one of the most interesting-and-odd things about me is that, thank God, I’m still alive.

2. Privilege and Accomplishment: From the ignoble to the proud. My second graduate degree is from Yale Divinity School, which looks like this.

I really loved the time I was able to spend at Yale. One of the neatest things was I got in on the last classes ever taught there by Abraham Malherbe, Brevard Childs, and Leander Keck. Along with colleagues like Robert Wilson, Wayne Meeks, and Christopher Seitz, they made up one of the best Bible Departments in the world. (Not that the School suffered when the next generation arrived: John J. Collins, Adela Yarbro Collins, Harry Attridge, Miroslav Volf, et al).

One of the University’s best-kept secrets is Victoria Hoffer, the lady who taught me Hebrew. A brilliant person and the mother of five, she’s one of those folks who can work on fifteen projects at once and get them all done on time, with flair, while smiling and well-dressed. Not to mention that she’s a terrific teacher and that she literally wrote the book on Biblical Hebrew. I’ll always thank God for her.

I should do more posts about my teachers. I didn’t say anything here about that other great school. No, not Harvard. It’s HARDING Graduate.

3. Bad habit: I’m what you might call “a hoarding messy.” (Try saying that with a high British accent). I irrationally hang on to all kinds of things. In fact, just about everything that comes into my possession I keep. And I don’t organize it very well. My wife will not allow my messy collections to take over the house, and I’ve actually developed some fairly-tidy habits there. But at my work office the demon runs wild. As I write this, my desk is piled about 4 inches deep in papers, folders, notebooks, etc., and there are nearly as many books stacked on the floor as there are on the shelves.

Now, that’s not particularly interesting, but there is an odd part here: there are pockets of my life where everything is immaculate. I’m very picky, for example, about what I eat, what I wear, written work, and presentations.

I sometimes comfort myself by remembering that people like me are said to be unusually creative. But most of the time, I just wish I would get a handle on my sloppy ways. And I worry. I worry about what this glaring bad habit says about my character and my inner world. I’m trying to do better.

4. Unforgettable experience: In the summer of 1985, I took five consecutive flights, over a period of 24 hours, and my ears wouldn’t clear. One flight attendant told me that giving me an aspirin was a no-no. At one point the pain was so terrible, I asked the Lord to just let me die.

Having made it from Manaus, Brazil to Altus, Oklahoma in that fashion, the next day I went to the doctor who gasped when he got a look at the raging infection in both of my ears. The day before my excruciating series of flights, I had gone with a group out onto the Amazon River. At the end of several hours on the water, the tour guide and captain stopped the boat’s engine and told us that if we wanted to tell our friends that we’d gone swimming in the Amazon, this was the time and place. I was one of the first to jump in.

Of course, not planning to swim in the river from which we had earlier pulled piranhas, none of us had a towel. I never thought to dry my ears. The big bad bugs of the Amazon went to work overnight, and I wound up learning some important lessons.

My ears got better. My life was forever changed by my experiences with the churches in Manaus and especially Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

5. Jobs: One of my first real jobs had me operating two commercial radio stations—one AM, one FM—for hours on end . . . by myself . . . for $3.50/hour. Hard to believe, but it’s true.

The AM was a Country & Western format--“KWHW 1450”--one of the truly great institutions of Altus. The FM was an automated Top 40. The intros and music for that station were purchased pre-recorded on these giant reel-to-reel tapes.

I would come to work at about 4:00 p.m. and record local news, sports, and weather, as well as the few commercials they’d let me do. Then, I’d put the carts into just the right slots in one of three huge carousels. The tapes and the carts had inaudible signals that tripped whatever was supposed to play next. That system for the FM station worked perfectly, almost all of the time.

At 6:00 p.m. I’d start a six-hour board shift on the AM, while minding the automated FM station that was broadcasting from literally the next room. For all of that time, I was the only person in the building (except for a couple of times I let a current girlfriend come in and check out the world of Mr. DJ; every job has its perks).

Long after midnight, the time when both stations signed off, I’d still be cleaning the machines, changing the tapes, and then setting up everything on the AM side for the morning man (the morning people are the prima Donnas of radio).

After several months of that, I told the program manager I was more than ready for that promised-but-overdue raise to $4.00/hour. With all the grace of a train wreck he let me know that I really hadn’t come along like he hoped I would and that he was reneging. I gave my two weeks notice on the spot. And so ended my glorious career in radio.

And here’s the tag: Ken Danley, Arlene Kasselman, Steve Duer, Greg Newton, and Royce Ogle? Yur-rit!

1. For starters: Some of the more interesting-or-odd things about me I just won’t tell here because they involve me breaking the law, acting immorally, being idiotic, or some combination thereof.

I sometimes think that God sends out Jack Bauer-type angels to protect young men during those high-testosterone years. (Their show would be called “At Least 24 Months”). Suffice it to say that one of the most interesting-and-odd things about me is that, thank God, I’m still alive.

2. Privilege and Accomplishment: From the ignoble to the proud. My second graduate degree is from Yale Divinity School, which looks like this.

I really loved the time I was able to spend at Yale. One of the neatest things was I got in on the last classes ever taught there by Abraham Malherbe, Brevard Childs, and Leander Keck. Along with colleagues like Robert Wilson, Wayne Meeks, and Christopher Seitz, they made up one of the best Bible Departments in the world. (Not that the School suffered when the next generation arrived: John J. Collins, Adela Yarbro Collins, Harry Attridge, Miroslav Volf, et al).

One of the University’s best-kept secrets is Victoria Hoffer, the lady who taught me Hebrew. A brilliant person and the mother of five, she’s one of those folks who can work on fifteen projects at once and get them all done on time, with flair, while smiling and well-dressed. Not to mention that she’s a terrific teacher and that she literally wrote the book on Biblical Hebrew. I’ll always thank God for her.

I should do more posts about my teachers. I didn’t say anything here about that other great school. No, not Harvard. It’s HARDING Graduate.

3. Bad habit: I’m what you might call “a hoarding messy.” (Try saying that with a high British accent). I irrationally hang on to all kinds of things. In fact, just about everything that comes into my possession I keep. And I don’t organize it very well. My wife will not allow my messy collections to take over the house, and I’ve actually developed some fairly-tidy habits there. But at my work office the demon runs wild. As I write this, my desk is piled about 4 inches deep in papers, folders, notebooks, etc., and there are nearly as many books stacked on the floor as there are on the shelves.

Now, that’s not particularly interesting, but there is an odd part here: there are pockets of my life where everything is immaculate. I’m very picky, for example, about what I eat, what I wear, written work, and presentations.

I sometimes comfort myself by remembering that people like me are said to be unusually creative. But most of the time, I just wish I would get a handle on my sloppy ways. And I worry. I worry about what this glaring bad habit says about my character and my inner world. I’m trying to do better.

4. Unforgettable experience: In the summer of 1985, I took five consecutive flights, over a period of 24 hours, and my ears wouldn’t clear. One flight attendant told me that giving me an aspirin was a no-no. At one point the pain was so terrible, I asked the Lord to just let me die.

Having made it from Manaus, Brazil to Altus, Oklahoma in that fashion, the next day I went to the doctor who gasped when he got a look at the raging infection in both of my ears. The day before my excruciating series of flights, I had gone with a group out onto the Amazon River. At the end of several hours on the water, the tour guide and captain stopped the boat’s engine and told us that if we wanted to tell our friends that we’d gone swimming in the Amazon, this was the time and place. I was one of the first to jump in.

Of course, not planning to swim in the river from which we had earlier pulled piranhas, none of us had a towel. I never thought to dry my ears. The big bad bugs of the Amazon went to work overnight, and I wound up learning some important lessons.

My ears got better. My life was forever changed by my experiences with the churches in Manaus and especially Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

5. Jobs: One of my first real jobs had me operating two commercial radio stations—one AM, one FM—for hours on end . . . by myself . . . for $3.50/hour. Hard to believe, but it’s true.

The AM was a Country & Western format--“KWHW 1450”--one of the truly great institutions of Altus. The FM was an automated Top 40. The intros and music for that station were purchased pre-recorded on these giant reel-to-reel tapes.

I would come to work at about 4:00 p.m. and record local news, sports, and weather, as well as the few commercials they’d let me do. Then, I’d put the carts into just the right slots in one of three huge carousels. The tapes and the carts had inaudible signals that tripped whatever was supposed to play next. That system for the FM station worked perfectly, almost all of the time.

At 6:00 p.m. I’d start a six-hour board shift on the AM, while minding the automated FM station that was broadcasting from literally the next room. For all of that time, I was the only person in the building (except for a couple of times I let a current girlfriend come in and check out the world of Mr. DJ; every job has its perks).

Long after midnight, the time when both stations signed off, I’d still be cleaning the machines, changing the tapes, and then setting up everything on the AM side for the morning man (the morning people are the prima Donnas of radio).

After several months of that, I told the program manager I was more than ready for that promised-but-overdue raise to $4.00/hour. With all the grace of a train wreck he let me know that I really hadn’t come along like he hoped I would and that he was reneging. I gave my two weeks notice on the spot. And so ended my glorious career in radio.

And here’s the tag: Ken Danley, Arlene Kasselman, Steve Duer, Greg Newton, and Royce Ogle? Yur-rit!

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

Karl Barth's Rejection of Natural Theology, 2

My previous two posts were about . . .

1. A general question I have about the place of apologetics, or “Christian evidences,” in the mission of the church.

2. The Christian theologian Karl Barth and his rejection of “natural theology,” trying to establish the existence of God by reason.

That second post (just before the one you’re reading) gives an overview of what Barth said was the first dilemma of the Christian who tries to convert another person by means of natural theology. Now for the second half of what Barth calls the “double dilemma.”

In a debate about the existence of God, says Barth, if the unbeliever realizes that the believer has no intention of giving up his belief even if his arguments fail, the unbeliever may become angry, and understandably so. Feeling as though he’s being toyed with, he will be hardened against the only saving truth.

On the other hand, if the points made by natural theology should “succeed,” there is no guarantee that the unbeliever will then be prepared “for the decision of faith” (93). As things turn out, unbelief might simply “take up its abode” (93) and become satisfied in the sphere of natural theology. Thus, having come to know some god or the other, the unbeliever never comes to know God. [As an “Exhibit A” someone might point to the many people who confess their belief in some “higher power” but who are obviously not Christians].

Barth says that there are two roots from which the plant of “Christian” natural theology grows. And both of them are bad:

1. A “Christian” natural theology does not rightly regard unbelief. For unbelief is not the result of the natural man failing his course in the philosophy of religion. Rather, unbelief is “active enmity against God.” It is not “a hopeful and lovable inexperience which can be educated above itself with soft words and in that way led at least to the threshold of faith” (94). Rather, unbelief “is hatred against the truth and therefore the deprivation of the truth” (95).

2. Second, and even more important, a “Christian” natural theology does not rightly regard God Himself. For the believer, the real God in whom faith believes “must be taken so seriously that there is no place at all for even an apparent transposition to the standpoint of unbelief, for the pedagogic and playful self-lowering into the sphere of its possibilities.” No human being ever stoops down in that way, but only “the real God alone, in His grace and mercy” (95).

So ends Karl’s critique of natural theology. Again I ask, Is Barth on target? Is he wrong? Some of both? I’m curious about what you think and why.

1. A general question I have about the place of apologetics, or “Christian evidences,” in the mission of the church.

2. The Christian theologian Karl Barth and his rejection of “natural theology,” trying to establish the existence of God by reason.

That second post (just before the one you’re reading) gives an overview of what Barth said was the first dilemma of the Christian who tries to convert another person by means of natural theology. Now for the second half of what Barth calls the “double dilemma.”

In a debate about the existence of God, says Barth, if the unbeliever realizes that the believer has no intention of giving up his belief even if his arguments fail, the unbeliever may become angry, and understandably so. Feeling as though he’s being toyed with, he will be hardened against the only saving truth.

On the other hand, if the points made by natural theology should “succeed,” there is no guarantee that the unbeliever will then be prepared “for the decision of faith” (93). As things turn out, unbelief might simply “take up its abode” (93) and become satisfied in the sphere of natural theology. Thus, having come to know some god or the other, the unbeliever never comes to know God. [As an “Exhibit A” someone might point to the many people who confess their belief in some “higher power” but who are obviously not Christians].

Barth says that there are two roots from which the plant of “Christian” natural theology grows. And both of them are bad:

1. A “Christian” natural theology does not rightly regard unbelief. For unbelief is not the result of the natural man failing his course in the philosophy of religion. Rather, unbelief is “active enmity against God.” It is not “a hopeful and lovable inexperience which can be educated above itself with soft words and in that way led at least to the threshold of faith” (94). Rather, unbelief “is hatred against the truth and therefore the deprivation of the truth” (95).

2. Second, and even more important, a “Christian” natural theology does not rightly regard God Himself. For the believer, the real God in whom faith believes “must be taken so seriously that there is no place at all for even an apparent transposition to the standpoint of unbelief, for the pedagogic and playful self-lowering into the sphere of its possibilities.” No human being ever stoops down in that way, but only “the real God alone, in His grace and mercy” (95).

So ends Karl’s critique of natural theology. Again I ask, Is Barth on target? Is he wrong? Some of both? I’m curious about what you think and why.

Monday, January 15, 2007

Karl Barth's Rejection of Natural Theology, 1

Why did theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) oppose the idea of trying to lead skeptics to Christ by first convincing them, apart from Scripture, of the existence of God? Whether you agree with Barth or not (and I find myself doing some of both), it’s hard to completely dismiss all of his point on this question.

Why did theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) oppose the idea of trying to lead skeptics to Christ by first convincing them, apart from Scripture, of the existence of God? Whether you agree with Barth or not (and I find myself doing some of both), it’s hard to completely dismiss all of his point on this question.As much as he wrote--literally thousands and thousands of pages—it’s certain that Barth’s thoughts on this subject can be found in more than one place. Here, I’ll be working from his Church Dogmatics, II/1, beginning at page 88.

One more thing. In what follows, I’ll be using the phrase “natural theology” a lot. Quite literally, “theology” means “words about God.” So what does “natural theology” mean?

In Millard J. Erickson’s terrific little book, Concise Dictionary of Christian Theology, the phrase “natural theology” is defined as “Theology developed apart from the special revelation in Scripture; it is constructed through observation and experimentation.” When it comes to the existence of God, the phrase “natural theology” assumes that people, even skeptics, can come to know about God through observation and reason. On to Karl Barth.

- - - - - - -

Before getting into Barth’s analysis of natural theology, the reader is immediately made aware of his opinion. He begins by asking whether the church should “try to find a readiness of God other than that which is present in the grace of His Word and Spirit” (88). With that sarcastic beginning, he launches an all-out assault. The entirely negative assessment here almost eliminates the distinction between analysis and critique. For Barth, to know natural theology is to hate it.

His analysis goes like this: To borrow a phrase from Paul (my analogy here), much as the law served as a schoolmaster who brought us to Christ, so natural theology can bring a natural person to Theology. That is, by first meeting God by means of natural theology—say, by participating in a fair debate about His existence—the natural person can sometime later come to know God as the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.

As Barth describes this ideal journey, the establishing of the God’s “knowability in the natural sphere” can function as “a preparation for the establishing of His knowability in His revelation” (89). Further, since leading people to the knowledge of God and thus to salvation is the “highest and most comprehensive work of love”(92), natural theology, which can serve as the way by which the unbeliever comes to faith, is not only legitimate. It is, according to this view, “necessary” (90). Not just a good idea, it is an obligation.

But, says Barth, the path known as natural theology invariably sets up a “double dilemma” (94). What does he mean by that? From the standpoint of the believer, to lead someone to the knowledge of God by means of natural theology is, again, something he is compelled to do. How could he be a person of true faith and love and do anything else?

And yet, ironically, this act of love requires the believer to speak falsely in behalf of the true God! That’s because the believer must use “the well-known artifice of dialectic” (93)—intellectual investigation through dialogue-- in order to bring the unbeliever to the decision of faith. This intrigue necessarily turns the believer into a hypocrite, because he must pretend that he doesn’t know what he certainly does know. That is, to proceed in his work of love, the believer must approach the unbeliever with a faith that is “masked as unbelief” (93). The believer pretends to occupy a position where “faith and unbelief have equal rights” (92).

Not only is this hypocritical, it also means that the believer assumes that he has a set of arguments that, at least in this case, is a necessary supplement to the truth of the gospel. But, says Barth, since the gospel is the unique and true self-revelation of God, such could never be the case. Why? Because: “When a man stands in the decision of faith or unbelief, he has not arrived at this position from any of the pre-decisions which are possible to him apart from God’s revelation” (91).

Furthermore, such a ploy entangles the believer in the sort of condescension that befits only God. Believers who use the tack of natural theology necessarily act as though they are superior to unbelievers. In practice, they deny that they are “poor sinners alongside other poor sinners” (96).

Okay, let’s stop here. We’ll take the second part of the “double dilemma” next time. At this point, do you agree or disagree with Barth? Specifically, is it Christian for a believer to enter into a debate about the existence of God when he has no real intention of giving up his beliefs if proven wrong? On the other hand, since the believer is certain that the true God cannot rightly be disproved, is it hypocritical for the believer to enter a discussion where the other side thinks that that is exactly what can happen?

Between the lines of this discussion, Barth seems to be asking, How could it ever be right and faithful for Christians to act as though they trust in human arguments before they trust in the gospel? Isn’t that an act of human pride? Doesn’t it involve the believer in thinking that he knows a better approach, forgetting that God has already drawn us to Himself by His Son and the Word of the cross? If the believer thinks, with Paul, that the gospel is “the power of God unto salvation” then why would he concoct or borrow something else and preach it instead?

Thoughts?

Friday, January 12, 2007

Natural Theology: Is it Christian?

Mike Cope set off quite a discussion yesterday when he quoted from a new book by Samuel Harris.

Harris recently gained a good bit of attention when he published “The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason.” His more-recent book—the one that Mike was quoting—is called “Letter to a Christian Nation.”

Except for the few snippets I’ve come across, I haven’t read either of Harris’ books. But I gather that both of them advance ideas like:

How should the church respond to the Samuel Harrises of the world (assuming that it should)? That is, given our situation, where unbelievers make public assertions designed to refute the claims of Christianity and embarrass the commitment of religious faith, how should Christians respond?

What does the way of Christ teach us about how to handle our ever-popular, in-the-news debates between faith and unbelief, reason and religion, science and Scripture?

Most of all, I come back to this question: To what extent is it Christian for believers, as part of the church’s evangelistic thrust, to advance and defend arguments for the existence of God?

Now, if you come from the same place I do, then you’re likely to say that it is only right for Christians to rationally advance theism. In fact, if someone says that he loves his neighbor as himself, and that he completely loves the God who saves us through His Son, how could that person do anything less than to try to convince the atheist or the agnostic of the existence of God? After all, once the unbeliever is convinced of the reality of God, that person can then be led to Christ, the Son of God.

It’s interesting. Karl Barth, the man regarded by many as the greatest Christian theologian of the 20th century, said that what I just described is not, in fact, Christian. Why did he say that? I’ll explain next time.

Harris recently gained a good bit of attention when he published “The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason.” His more-recent book—the one that Mike was quoting—is called “Letter to a Christian Nation.”

Except for the few snippets I’ve come across, I haven’t read either of Harris’ books. But I gather that both of them advance ideas like:

- Biblical religion is deeply flawed. In fact, it’s just plain bad. If someone had to pick a religion to practice, there are better choices than Christianity.

- In practice, Christians renounce what they say they believe and are committed to. They don’t practice what they preach.

- The commonly-known Christian variety of supernatural theism—where, for example, people can pray expecting that God will act in response, even transcending the laws of nature—is irrational.

How should the church respond to the Samuel Harrises of the world (assuming that it should)? That is, given our situation, where unbelievers make public assertions designed to refute the claims of Christianity and embarrass the commitment of religious faith, how should Christians respond?

What does the way of Christ teach us about how to handle our ever-popular, in-the-news debates between faith and unbelief, reason and religion, science and Scripture?

Most of all, I come back to this question: To what extent is it Christian for believers, as part of the church’s evangelistic thrust, to advance and defend arguments for the existence of God?

Now, if you come from the same place I do, then you’re likely to say that it is only right for Christians to rationally advance theism. In fact, if someone says that he loves his neighbor as himself, and that he completely loves the God who saves us through His Son, how could that person do anything less than to try to convince the atheist or the agnostic of the existence of God? After all, once the unbeliever is convinced of the reality of God, that person can then be led to Christ, the Son of God.

It’s interesting. Karl Barth, the man regarded by many as the greatest Christian theologian of the 20th century, said that what I just described is not, in fact, Christian. Why did he say that? I’ll explain next time.

Monday, January 08, 2007

Religion Courses at Amarillo College

Spring Semester, Jan. 16– May 11, 2007

Day Classes

RELG 1303 The Prophets 9:00-10:15 MW

PHIL 1304 World Religions 1:30-2:45 MW

RELG 1302 New Testament 9:00-10:15 TTh

Evening Class

RELG 1301 Old Testament 7:00-9:45 pm Tues.

Did you know? . . . .

All of the above classes (except “The Prophets”) may be taken for Humanities credit and will apply toward any degree program.

All course work is guaranteed to transfer to any college or university in Texas.

Pre-registration is underway, and classes begin Tuesday, January 16, 2007.

Students at Amarillo College may choose to major in Religion.

Classes may be taken for “Leisure Studies” credit, and anyone is welcome to simply audit course free of charge.

For more information, you may call the Amarillo Bible Chair at (806) 372-5747. Speak with either Frank or Becky.

To find out more about registration and enrollment, see the Amarillo College website.

Day Classes

RELG 1303 The Prophets 9:00-10:15 MW

PHIL 1304 World Religions 1:30-2:45 MW

RELG 1302 New Testament 9:00-10:15 TTh

Evening Class

RELG 1301 Old Testament 7:00-9:45 pm Tues.

Did you know? . . . .

All of the above classes (except “The Prophets”) may be taken for Humanities credit and will apply toward any degree program.

All course work is guaranteed to transfer to any college or university in Texas.

Pre-registration is underway, and classes begin Tuesday, January 16, 2007.

Students at Amarillo College may choose to major in Religion.

Classes may be taken for “Leisure Studies” credit, and anyone is welcome to simply audit course free of charge.

For more information, you may call the Amarillo Bible Chair at (806) 372-5747. Speak with either Frank or Becky.

To find out more about registration and enrollment, see the Amarillo College website.

Friday, January 05, 2007

Where Would Jesus Shop?

Where Would Jesus Shop?

Check out this ad that has generated quite a bit of reaction. Is it kingdom business for a church to encourage a boycott of the likes of Walmart? Assuming that there are such circumstances, does a Christian indictment of Walmart stick? What do you think?

Check out this ad that has generated quite a bit of reaction. Is it kingdom business for a church to encourage a boycott of the likes of Walmart? Assuming that there are such circumstances, does a Christian indictment of Walmart stick? What do you think?

ISBE on the Web

Something I didn’t realize until a few days ago: the old International Standard Bible Encyclopedia is available free on-line. No, it’s not the updated, much-newer one. But the original ISBE is loaded with a lot of still-good stuff for the would-be Bible student.

One of the finest multi-volume works of biblical scholarship from the early 20th century, it features articles by some of the best and brightest of that day: George L. Robinson, Benjamin B. Warfield, A. T. Robertson, the list goes on.

Actually, it can be found at two or three different places on the web. You can check it out at the following: http://www.studylight.org/enc/isb/ Happy studying!

One of the finest multi-volume works of biblical scholarship from the early 20th century, it features articles by some of the best and brightest of that day: George L. Robinson, Benjamin B. Warfield, A. T. Robertson, the list goes on.

Actually, it can be found at two or three different places on the web. You can check it out at the following: http://www.studylight.org/enc/isb/ Happy studying!

The Gospel of Judas, 1

Last night, I read “The Gospel of Judas.” A little bit about it.

An English translation of this mid-second century document was first published just last year. Why not before? Because for about 1,600 years, it was completely lost.

It was only within the last few decades that a single manuscript turned up on the antiquities market. And by the time it was recognized as an ancient copy of “The Gospel of Judas,” the manuscript was in such bad shape it had to be pieced together again (using tweezers!) over a period of several years.

Of course, then, for our purposes, the ancient Coptic manuscript had to be translated into English. For what it’s worth, scholars say that our one manuscript actually reflects a translation into Coptic from the document’s original language, Greek. So reading it in English, we’re actually two languages away from the original.

Anyway, for a full account of the rediscovery, reconstruction, and eventual publication of “The Gospel of Judas,” apparently the best place to go is Herbert Krosney’s book, The Lost Gospel: The Quest for the Gospel of Judas Iscariot (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006).

I suspect that many theologically-conservative Christians will immediately want to read N.T. Wright’s new book, Judas and the Gospel of Jesus: Have We Missed the Truth about Christianity? (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2006). That way they’ll have the Wright take on the whole thing. But remembering something I once heard Everett Ferguson repeat—that one word in the primary source is worth a 1000 words in a secondary source—I made myself just read the text first. You can too.

Without having to purchase all of the debatable “Introduction” and “Commentary” sections of the print edition--The Gospel of Judas (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006)--you may read the English translation here.

Within the next few days, I’ll mention some of my first reactions to “The Gospel of Judas” and what’s been made of it since it first came out.

An English translation of this mid-second century document was first published just last year. Why not before? Because for about 1,600 years, it was completely lost.

It was only within the last few decades that a single manuscript turned up on the antiquities market. And by the time it was recognized as an ancient copy of “The Gospel of Judas,” the manuscript was in such bad shape it had to be pieced together again (using tweezers!) over a period of several years.

Of course, then, for our purposes, the ancient Coptic manuscript had to be translated into English. For what it’s worth, scholars say that our one manuscript actually reflects a translation into Coptic from the document’s original language, Greek. So reading it in English, we’re actually two languages away from the original.

Anyway, for a full account of the rediscovery, reconstruction, and eventual publication of “The Gospel of Judas,” apparently the best place to go is Herbert Krosney’s book, The Lost Gospel: The Quest for the Gospel of Judas Iscariot (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006).

I suspect that many theologically-conservative Christians will immediately want to read N.T. Wright’s new book, Judas and the Gospel of Jesus: Have We Missed the Truth about Christianity? (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2006). That way they’ll have the Wright take on the whole thing. But remembering something I once heard Everett Ferguson repeat—that one word in the primary source is worth a 1000 words in a secondary source—I made myself just read the text first. You can too.

Without having to purchase all of the debatable “Introduction” and “Commentary” sections of the print edition--The Gospel of Judas (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 2006)--you may read the English translation here.

Within the next few days, I’ll mention some of my first reactions to “The Gospel of Judas” and what’s been made of it since it first came out.

Thursday, January 04, 2007

Xmas is Over!

A belated “Happy New Year!” I hope your 2007 is off to a good start.

The last two weeks brought me a predictable change of pace. It was a good thing, I guess. But I crave my routines, don’t you?

Not to mention that there’s a lot about the holidays that I absolutely hate, the part that C. S. Lewis distinguished as “Xmas” as opposed to “Christmas.” That is to say, I like wonder but not worry, sharing but not over-spending, feasting but not gorging, traveling but not rushing.

I think about all of the stories and statistics I’ve heard over the years about people putting on weight and overspending in the season just past. And then there’s all of the drinking that turns people into menaces and puts all the rest of us on high alert. What’s good about that?

I remember one of my church elders in Connecticut who without blinking would say, “I hate Christmas.” Yet, during our Sunday-night-before-Christmas devotionals, no one sang about Jesus Christ with more gusto and spirit than he did. He loved Christmas. He hated Xmas.

The last two weeks brought me a predictable change of pace. It was a good thing, I guess. But I crave my routines, don’t you?

Not to mention that there’s a lot about the holidays that I absolutely hate, the part that C. S. Lewis distinguished as “Xmas” as opposed to “Christmas.” That is to say, I like wonder but not worry, sharing but not over-spending, feasting but not gorging, traveling but not rushing.

I think about all of the stories and statistics I’ve heard over the years about people putting on weight and overspending in the season just past. And then there’s all of the drinking that turns people into menaces and puts all the rest of us on high alert. What’s good about that?

I remember one of my church elders in Connecticut who without blinking would say, “I hate Christmas.” Yet, during our Sunday-night-before-Christmas devotionals, no one sang about Jesus Christ with more gusto and spirit than he did. He loved Christmas. He hated Xmas.

The holiday season is over. I’m glad Xmas is too. Aren’t you?